Many nurses are continuing to raise their voices about what they perceive as unsafe staffing levels in hospitals. Lisa Cornelius, a registered nurse at Mountain View Hospital in Las Vegas, recently told Spectrum News that “There’s not really a staffing shortage. There’s a shortage of nurses who are willing to work under the conditions the way that they are in the hospitals today.”

Cornelius, speaking at a recent rally organized by National Nurses Organizing Committee/National Nurses United, said she is sometimes tasked with caring for up to twice as many patients as would normally be standard.

Another nurse at the same rally, Hannah Drummond, who is a chief nurse representative at her hospital in Asheville, N.C., told Spectrum News, “In the ER, we’re cleaning our own room. I’m my own phlebotomist, I’m my own CNA or patient care tech.”

A recent panel discussion hosted by the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania delved into the nursing shortage and offered some ideas for policymakers, health systems and educational institutions to address it.

One reason cited for a shortage is nurse burnout. But Karen Lasater, Ph.D., R.N., associate professor at Penn Nursing and a fellow of the American Academy of Nursing, gave a specific definition of that term.

“We know that burnout is a state of emotional exhaustion. It's brought on by prolonged or repeated stress, and it results in depersonalization, cynicism, and a lack of engagement and work,” Lasater said. Burnout is the result of avoidable occupational stress that's caused by system failures, she said. “It's those system failures that are interfering with the nurses’ ability to do their work effectively. It's really important to note that burnout is not the result of individual failings or lack of resilience. So any interventions that are targeted at the individual level — trying to boost someone's resilience — is not an effective strategy to reducing burnout.”

Lasater said the research is clear on the driving factors of nurse burnout is clear. The number one factor is unmanageable workloads in the context of poor work environments. “It's not the work itself being difficult, but rather the organizational failures that are hindering nurses from doing their work effectively that drive nurses to feel burned out,” she said.

Some of the interventions hospital executives talk about for reducing or preventing burnout don’t appeal as much to nurses when they are surveyed, she said. “There's a real mismatch in what hospitals think they should do and what nurses want them to do. Nurses said appointing clinician wellness champions is not effective; providing resiliency training is not effective. Those are interventions that are really targeting the individual, as opposed to addressing dysfunctions at the organization level that are putting this undue stress on frontline workers who are being hampered and doing their jobs effectively,” she said. “If hospitals and other employers of nurses are really serious about addressing the drivers of burnout, they really need to dispense with these ideas of throwing pizza parties and doing resiliency trainings, and instead be responsive to what nurses say they need, which is manageable and safe workloads.”

Bianca Frogner, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and director of the Center for Health Workforce Studies at the University of Washington, said there also needs to be more attention on nursing shortages in long-term care, especially skilled nursing facilities. “We have not paid enough attention to what's happening in long-term care. I often reflect on the past few years, and think what did we learn or gain out of this pandemic? Do we learn anything? And are we changing anything? And I think most people in the room would say not really,” she said. “And I think in long-term care, that's been particularly surprising given just what a mess it has been in that area throughout the pandemic. I think part of it is this question of political will. Where is the political will to make some of the changes? And what is the story that we need to be telling to get there? And I have to say, I'm a little puzzled.”

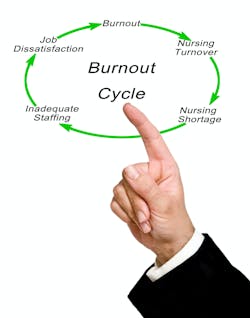

Lasater described a vicious cycle where nurses working in bad environments leave and tell other nurses not to go work in that hospital, and it results in the nurses who stay there having even worse working conditions and even lower morale. “If I were a hospital administrator, I would try to be proactive and address the reasons why nurses are leaving,” she said. “I think this is a retention issue. I do not think it's a pipeline issue, and I do not think it has to do with how we are training nurses to enter the workforce.”

A looming question is how can hospitals afford to pay for more nurses?

Lasater said the research shows that when nurses are present in more numbers at the bedside, care gets delivered more efficiently. Patients have shorter lengths of stay, so patients get out of the hospital sooner. “And that’s serious cost savings for the hospital. Patients are less likely to be readmitted to the hospital. Medicare and other payers are saving big money when patients don't get readmitted. So there are lots of ways in which hospitals stand to financially benefit when they invest in nursing,” she said.

An enormous amount of money flows through hospitals and other healthcare systems, and we often don't have good outcomes and good quality to show for it, Lasater added. “Nurses are the reason that patients go to hospitals. The reason you're in a hospital is because you need nursing care. So if hospitals aren't investing in their nursing care, where is that money going? I think there's an opportunity to have greater accountability about how hospitals are investing their money and where it's going, if not to nursing.”

Moderator Rachel Werner, M.D., Ph.D., executive director of Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute, asked panelists to suggest one state or federal policy change that they think would meaningfully address the nursing workforce shortage, and how optimistic they are that change might happen.

Lasater said her policy change would be either state or federal requirements for minimum safe staffing in hospitals. “I'm pretty optimistic about this for a number of reasons,” she explained. “There are more and more states pushing for this legislation. For those of us here in Pennsylvania, you should know that it's passed in the House for the first time ever, and it's on its way to the Senate. It's called the Patient Safety Act, and it would require hospitals to staff enough nurses to safely care for patients. The only state in the country to have this kind of legislation is California. It's had it for two decades now, to good effect. Patients in California get three more hours of nursing care a day compared to patients in other states, and Oregon will be joining in that this summer. So I have optimism that we're moving in the right direction. Also, the American Nurses Association has endorsed this legislation on a federal level for the first time in a long time, which represents a major historic shift in their position. I'm optimistic because I know that the public knows how important nurses are in patient care, and they understand now more than ever, I think, because of the pandemic that if we don't have nurses at the bedside, public health is going to suffer.”

Gopi Shah Goda, Ph.D., a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research at Stanford University said she would second the idea of changing minimum staffing ratios, but perhaps also tied with some kind of funding source for that — increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates or having some kind of dedicated financial incentives to help companies and hospitals do that could make that even more effective. “I think we all know that sometimes unfunded mandates are hard to fill, especially in the current environment of staffing shortages or labor shortages in the economy more generally,” she said. “If we're thinking long-term, the evidence on increasing immigration flows is also very convincing that this could effectively lead to more both RN and CNA hours per nursing home resident. It’s not an immediate fix, but it's something that could potentially help in the long run.”

David Benton, Ph.D., R.N., former CEO of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, said that for him, it’s about finding a long-term solution.

“We actually know what the long-term problems are going to be. If you look at the 2050 projections for the numbers of individuals we have and the age bands that they will be in, then the current model is simply not sustainable. The population support ratio is going to halve in the next 20 years, and therefore the competition for workers within the health sector is going to become even more acute,” he said. “So we're going to have to actually fundamentally rethink the way that we deliver care and the way that we educate practitioners in a way that actually enables us to optimize the usage of of the population that we've got. We're going to have to look for solutions that other countries that have faced this problem for some time have started to use by using technology, where increased monitoring at a distance could take place or individuals can actually prioritize their visits as part of that process, and using technology that will alert us when things start to go wrong. We know that the U.S. and many other countries have got huge obesity problems. And that is actually adding to the long-term labor burden that there will be within the health service. So there are many things that policymakers could do, but they've got to stop using a Band-Aid solution that actually is only thinking about their next election cycle and actually thinking about the health and well being of citizens into the future.”